The July 2008 Challenge

Design an original game. It can be a board game, card game, party game, drinking game, computer game or whatever. Provide images (photographs, drawings, or rough sketches) of any equipment, such as boards or pieces, that would be needed in order to play.

The Results

Ryan Finholm

3-2-1 POKER

This is best as a two-player game.

Equipment

One regular deck of playing cards (with no jokers).

Objectives

- To get the best poker hand.

- To win the most rounds per deck of cards (there are five rounds per deck, three or more rounds wins the deck).

- To win the majority of the decks of cards played.

Game Play

The cards are shuffled, and five cards are dealt facedown to both players.

Both players pick up and study their hands.

Each player chooses exactly three cards from their own hand to pass to the other player. Players may not collect their opponent’s cards until they have passed the three cards from their own hand, facedown, to the next player.

The players incorporate the three cards passed by the opponent into their own hand.

Each player then chooses exactly two cards from their own hand to pass to the other player. Players may not collect their opponent’s cards until they have passed the two cards from their own hand, facedown, to the next player.

The players incorporate the two cards passed by the opponent into their own hand.

Each player then chooses exactly one card from their own hand to pass to the other player. Players may not collect their opponent’s card until they have passed the card from their own hand, facedown, to the next player.

The players incorporate the card passed by the opponent into their own hand.

Both players show their hands. The best final poker hand wins.

Tips and Reminders

Players must pass three cards, then two cards, then one card as specified in the above rules, no more and no fewer, no matter what their hand is. For example, if a player has a flush, straight, or full house before the last cards are passed, that player will have to break up the hand.

The game can be played with three or more players, but is best as a two-player game. If played with more than two players, cards should be passed clockwise for the first pass, counter-clockwise for the second pass, and clockwise again for the third pass. No matter how many people are playing, the game should not be played with more than one deck. Card counting is encouraged.

This game can involve an ante and bets after the hands are dealt and/or reformulated, but this is not recommended. Betting tends to interrupt the flow of this otherwise quick and engaging game.

After the final card is exchanged in a game, the players must show their hands — they cannot simply fold and discard their hand face down into the discard pile. Card counting is encouraged, and each player should start each round with the same information as their opponent.

DEFEND THE BISHOP

A two-player game.

Equipment Needed

- One chess board/checkerboard (or half of a board).

- Two black pawns.

- Two white pawns.

- One black knight.

- One white knight.

- One black bishop.

- One white bishop.

- One die

Objective

To get your bishop to the very last square of the board (the lower left-side square), while your other three pieces are still on the board.

Starting Game Play

The players decide if they want to play with a half of the chessboard or a full chessboard. Half-board games are recommended. Full-board games might last quite a bit longer than half-board games.

Each player rolls the die. The higher roller starts. If there is a tie, re-roll.

The starting player chooses either the white or black set of chess pieces.

The starting player then rolls the die, and chooses whichever piece he wants to move that many spaces forward on the board.

Play moves to the next player, who rolls the die and chooses whichever piece he wants to move that many spaces forward on the board.

Movement Along the Board

Players may only move their pieces forward on the board. The only time a piece is moved backwards is during a tied attack (see below). The movement of the pieces will always snake down the board horizontally from left to right on the topmost set of squares, then down one row and horizontally from right to left on the second set down, etc.

At each following turn, the players roll the die and either move a piece onto the board, or move a piece that is already on the board further ahead.

No player may ever pass a turn. After the die is rolled, one or another of the player’s pieces must be moved that number of spaces, even if every possible option will produce an unwanted result.

Attacks

If a player moves a piece to an occupied space, his piece ‘attacks’ the other piece (please note that pieces will pass each other without attacking, but they must attack if the die roll ends the piece’s movement on an occupied square). The knights are the strongest pieces and the bishops are the weakest pieces. The results of the attacks are always as follows:

- The knight beats the pawn

- The knight beats the bishop

- The pawn beats the bishop

If the pieces are the same, the battle is tied. The winner takes the disputed square, and the loser is removed from the board. In the case of a tie, the attacker takes the disputed square, and the original occupant of that square moves backwards one space.

No square may ever be occupied by more than one piece.

If a player is compelled to move his piece onto a space occupied by one of his own other pieces, he must attack his own piece, with the same results as those noted above.

Pieces that are removed from the board due to attacks are still in the game; on successive turns, the player can use their turn to re-introduce such a piece to the board. Players will only ever use and hold their own pieces. A player’s piece can never be captured, killed, or stolen by the opponent.

Slippery Squares

All of the squares at the leftmost and rightmost edges of the board are ‘slippery’. Any piece landing on one of those squares ‘slips off’, and is removed from the board.

If a player is forced onto a slippery square due to a tied attack, that piece is removed from the board. If a player is forced to move a piece onto a slippery square because each of the player’s pieces are aligned on the board in such a way that whichever piece the player chooses will end up on a slippery square, then the player must choose a piece to slip off the board.

Pieces that are removed from the board due to slippery squares are still in the game. On successive turns, the player can use their turn to re-introduce such a piece to the board.

The Last Square on the Board

The last square on the board is the bottom, left-most square.

To win, a player’s bishop must land on the last square of the board by an exact die roll, and each of the player’s other pieces must be somewhere on the board.

If a pawn or knight lands on the very last square of the board by an exact die roll, that player may instantly transport that piece to any ‘slippery’ right- or left-edge square of the player’s choosing. The player must then, during that same turn, roll the die again to move that pawn or knight off of that slippery square before play moves to the other player. The player must move the piece to a specific slippery square prior to rolling the die, and the player must move that piece the number of spaces on the subsequent die roll, even if it results in the player attacking his own piece or any other unwanted result. The player also has the option of removing that piece from the board instead of rolling – but the player must decide this before rolling the die. If the player decides to remove the piece from the board, play immediately moves to the other player.

If a bishop lands on the last square of the board when one or more of that player’s other pieces are off the board, that bishop is treated the same way that a pawn or knight landing on that last square would be treated (see above).

If a piece is moved past the last square on the board, it is removed from the board. Pieces that are removed from the board for moving past the last square are still in the game. On successive turns, the player can use their turn to re-introduce such a piece to the board.

Tips, Esoteric Rules, and Things to Keep in Mind

Die roll movements cannot be split between pieces. If a player rolls a six, one piece must be moved six spaces (or off the board if near the end of the last row, as applicable). If a player rolls a six, the player may not move two different pieces three spaces each.

It is possible that if the game pieces are lined up in a certain way, a short chain-reaction of forced attacks can occur. Regardless of the series of attacks and the outcomes, after the series of attacks is completed, play moves to the next player, and never back to the player who rolled the die last. The only times that players will roll twice in a row during one turn is if they choose to do so after one of their pieces lands on the very last square of the board (see above).

If a weaker piece attacks a stronger piece, that weaker piece is automatically removed from the board.

If a player has no game pieces on the board and rolls a ‘one’ on the die, whichever piece he chooses to place on the board will slide right back off, and play moves to the next player.

Players are allowed to attack their own pieces on purpose, and might choose to do so for strategic reasons.

Only the far left and far right edge squares of the board are slippery. The top and bottom rows are not slippery (except for the first and last squares of the rows).

Players are allowed to move their pieces to slippery squares (and, in doing so, remove them from the board) on purpose, and might choose to do so for strategic reasons.

The board does not ‘wrap around’. If a piece is moved past the last square on the board, it is removed from the board and any remaining moves on the die are lost.

Brian Raiter

WORD SQUARE

A game for two players.

Equipment

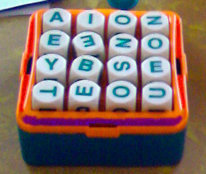

A box and set of 16 dice from a standard Boggle game. The edges of the Boggle board should be alternately colored red and blue.

Rules

One player is assigned to be Red and the other Blue. (Note that the colors are required simply to provide a sense of reference. If players prefer not to mark up their Boggle sets, the two assignments can be Across and Down, presuming the seating arrangements makes this unambiguous. Or they can be North-South and East-West, or for that matter This Way and That Way, accompanied with appropriate hand gestures.)

The Red player shakes the dice and sets out the resulting board.

Players then take turn selecting two dice from the board and transposing them, i.e. putting each one in the other’s cell. The dice may not be turned at any point during game play after the initial board is created. Players may choose any two dice to transpose, with the exception that they may not just undo the previous move made by the other player.

The object of each player is to maximize the number of words running parallel to the direction of their assigned color. Words are only scored that run the entire length of the board; there are no points scored for words shorter than four letters, or for words that do not proceed in a straight line.

Proper nouns, contractions, hyphenated words, and non-English words are not valid. If there is potential for disagreement on what constitutes a legal word, players should agree on a dictionary or word list before the game begins.

A player is permitted to pass when it is their turn to transpose letters. If both players pass in succession, the round ends immediately. Otherwise, the round ends when both players have had five turns. When the round is over, the board is scored and points are awarded. A player receives a multiplicative factor of two for each word in their color’s direction. Thus:

- If a player has formed 1 word, they receive 2 points.

- If a player has formed 2 words, they receive 4 points.

- If a player has formed 3 words, they receive 8 points.

- If a player has formed 4 words, they receive 16 points.

In addition, a player who manages to form 4 words in their direction will also receive half of the points awarded to their opponent for words formed. In the case where the ending board has eight legal words, both players receive the maximum of 24 points.

At the end of the round, the players exchange colors and a new round begins.

The game ends when one player reaches 50 points and is declared the winner. (The goal of 50 points can be raised or lowered as the players’ time and interest permit.)

Variant Versions

- Instead of a set number of turns to transpose dice, give each player an unlimited number of turns, but set a time limit of three minutes (using the standard Boggle timer).

- Give each player an unlimited number of turns, but with the added restriction that the board can never be returned to a configuration that it was in previously. A round only ends when both players pass. This version requires much more mental bookkeeping, and may not be socially feasible except as a computer-mediated game.

- Play each round normally, but at the end of the round, a timer is turned over and the players play a round of standard Boggle. The score for the round is thus the combined score.

My original plan had been to write a computer game, one that I’ve had in the back of my mind to do for the last ten years. But I just didn’t have the opportunity to work on it: right at the start of the month I gotten sucked into a project that consumed all my free time. (It may not surprise you to learn that one of the aspects of this project involves the rearrangement of letters in a two-dimensional grid.)

Anyway, about the entry that I did submit:

I was thinking about games that require a mix of both cooperation and competition. Wholly cooperative games can be fun and all, but to my mind the best games are ones that are basically competitive but still require the players to frequently cooperate in order to do well. I wanted there to be a bit of a prisoner’s-dilemma flavor to my game.

Making word squares is a delicate business, even when you have a free choice of words. The fact that each player can only make five exchanges is meant to push them to make moves that are to both players’ advantage, and so encourage the other player to let the exchanges stand as much as possible. The ideal move is the one that the other player can’t afford to undo, yet likely wouldn’t have made themselves because it gives you a marginally greater advantage.

The exponential scoring, and the “profit-sharing” bonus for completely filling the square for your direction, are also meant to encourage working with your opponent’s goals in mind in order to get ahead.

Unfortunately, I only know enough about game design to know that game balance is almost impossible to achieve when you don’t know any more than that. For example: Having a cap on the number of turns means that on the last move of a round, a player has little incentive not to sabotage the board. This problem is addressed with the variant rule that allows unlimited turns per round, but then it becomes cumbersome to avoid falling into repetitious moves, where both players are trying to get that one S into their preferred position.

Also, as someone who’s played quite a lot of Boggle in my time, I know that the dice have a wide variance in the raw materials they deliver. Word squares require a precise mixture of consonants and vowels, much like car engines require a precise mixture of fuel and air. Every now and then you get a board with a three vowels and thirteen consonants, or the other way around. Such boards would no doubt be very low-scoring, but I think they would still be fun to play out, and in fact the extra difficulty might encourage cooperation even more than usual. That said, this game might be better served by having a set of dice specially made to serve the needs of building word squares. I don’t have the statistical data necessary to determine what they would be, though.

But the main problem with my entry is that it seriously needs some playtesting in order to identify the hurdles and refine the concept. Unfortunately I didn’t have anyone to play it with, so none of that has been done. I almost didn’t submit anything this month because of that (it’s been over a year since I’ve missed a month). But then I remembered that one of the philosophies of the Commuter Challenge is that it’s always better to submit something instead of nothing — even when that something is lame. And so here I am.

by Brian — 7 August 2008 @ 02:17

Brian was nice enough to point out that my “3-2-1 Poker” is almost exactly the same as “Pass the Trash” poker, which has apparently been around just about forever. To the best of my recollection, I have never heard of or played “Pass the Trash”, though I guess it’s just as likely that I simply don’t remember having played it. Regardless, “3-2-1 Poker” is infinitely better, because players are dealt only 5 cards – in “Pass the Trash” players are dealt 7 cards and otherwise play by exactly the same rules. With only five cards it is more likely that you will have to break up a good hand. If you are dealt 2 pair, you will either have to give away a pair, or split up both pairs and hope that one of the cards comes back to you. If you get a straight or flush before the last pass, you will have to ruin your hand. It is vitally important to remember what you passed. None of these key attractions are present in “Pass the Trash”. I’m still going to highly recommend “3-2-1 Poker”; it’s great fun as a two-player, non-betting game.

I also need to clarify that in “Defend the Bishop”, at the very beginning of the game all pieces are off the board. Each piece has to be introduced to the board via die rolls on successive turns.

Also, the title “Defend the Bishop” is misleading. It is pretty much impossible to actually defend the bishop in any way, as would become clear during any game. The bishop is the weakest piece, so there is never really any reason for any other piece to avoid attacking it. I only named the game “Defend the Bishop” in order to reference a ribald inside joke.

by RyanF — 11 August 2008 @ 00:46